Everyone knows how important oil and air filter changes are to the well-being of a motorcycle. Checking the condition of brakes, greasing the pivot points in the frame and keeping clean fuel in the intake system, are all tops on the list of tasks that must be done to make sure a customer’s ride is ready to go when they want to get on it.

But what about that oft-neglected task way down on the list in the periodic maintenance table, checking all the nuts and bolts on the machine? Not very exciting, huh? It’s so much more interesting to get into a debate over what kind of oil to use than what kind of wrenches to spin, but keeping everything properly tightened should be high on the list of maintenance chores if you want every ride to be trouble free.

Any good motorcycle mechanic should make it a habit to do a slow walk around after every service, and at least check every nut and bolt they can see. In many cases you should check the nuts and bolts you can’t see as well. The first items that come to mind are exhaust system mounting bolts, especially if the machine is fitted with an aftermarket exhaust. Pipes and mufflers fight a constant battle between the conflicting vibrations of the engine on one end and the punishment of the road on the other. Another sensitive point is the rear subframe or rear carrier, especially on a machine that carries luggage of any sort. Having a loose bolt break off or a frame tube crack from errant vibration is sure to slow down a journey and ruin a lot of fun.

A good mechanic can go through a chassis and check all the nuts and bolts by feel, but a great mechanic has a torque wrench in his hand and the machine’s torque specifications page open on the workbench. There is no substitute for knowing exactly how tight sensitive nuts and bolts are when you’re finished with the job. The object is not to tighten every nut as tight as you can possibly make it, but to get it right.

Our house mechanic admits that he can go through any ATV, motorcycle or scooter and torque common nuts and bolts to 7 to 10 foot-pounds all day long with a standard ratchet in his hand, just by experience. But when a fastener calls for anything less or more, he reaches for the torque wrench. There’s a huge difference between 55 foot-pounds, which you might see on a torque spec for a suspension pivot bolt, and 55 inch-pounds, which would suit a brake bleeder nipple just fine. The difference between the two specifications can mean a suspension bolt that falls out or a bleeder nipple broken off.

As a group of folks who spend their days reading through factory and aftermarket motorcycle manuals digging out hard numbers, we can offer one uncomfortable tip, though: Be familiar with the common torque specifications for general nuts and bolts. As in, a typical plain carbon steel 6 x 1.0 mm bolt wants to be tightened to a maximum of 4.0 foot-pounds. If you have your factory manual in hand, and it’s telling you the 6 x 1.0 bolt you’re looking at should be tightened to 41 foot-pounds, you should investigate a little more before you attack it with the wrench. Yes, there are typos and mistakes in factory manuals, and blindly following an instruction to crank 41 foot-pounds into a 6 x 1.0 mm bolt will always break it off. Be aware that anything written down that seems suspect can very easily be an error just waiting to do you harm. Most manufactures also offer a general torque specification table based on thread size you can use to for unspecified fastener torque as well as a benchmark for torque specs that my appear inaccurate.

A sharp eye and a careful hand can find questionable fasteners quickly, and give you a chance to avert disaster later on. Every mechanic should have a tap and die set on hand, metric and SAE, to deal with thread difficulties that may come up. Running a tap through a set of balky threads will often clean up a problem waiting to happen, and it only take a few minutes if the tools are handy.

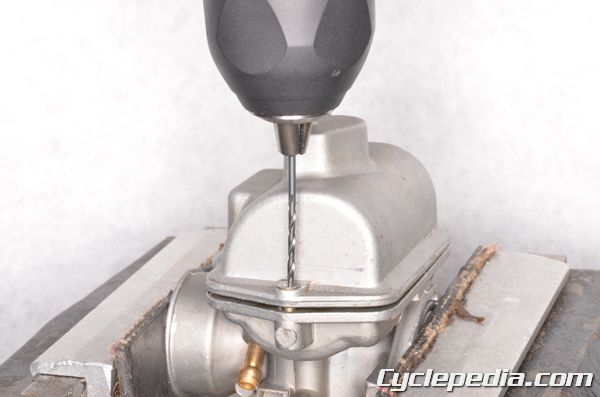

In the event that a broken-off bolt is found, it’s good to also have a set of Easy-Outs on hand, along with knowledge on how to quickly extract a broken bolt shaft without piling up a huge amount of hours. Thread insert kits are handy too, for those situations where there’s just no saving a boogered connection.

The key is to try to address every problem possible while the motorcycle is already on the lift, and not to get the customer’s bike out the door only to see it next week—with an angry customer wondering why you didn’t address the issue when you last saw the bike. A careful eye, and a careful hand armed with a torque wrench, can save your customers trouble and frustration down the road, while improving your reputation for paying attention to all the little details.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.